5 Main Metals Separated by Magnetic Separation: An Industrial Processing Guide

In the field of mineral processing and solid waste resource recovery, efficiency is the only metric that matters. Magnetic separation remains one of the most reliable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly methods for concentrating ores and purifying materials. However, a common misconception in the industry is that magnets are only useful for iron. From our experience at ORO Mineral Co., Ltd., we know that the application of magnetic fields extends far beyond simple ferrous recovery.

By manipulating magnetic field intensity—ranging from low-intensity drum separators to high-gradient wet separators—we can isolate a variety of paramagnetic and ferromagnetic materials. This article provides a technical breakdown of the 5 main metals separated by magnetic separation, detailing the mineralogy, the required gauss levels, and the specific equipment necessary for optimal recovery.

- 1. The Science of Magnetic Susceptibility

- 2. Iron (Fe): The Ferromagnetic Standard

- 3. Manganese (Mn): The Paramagnetic Challenge

- 4. Titanium (Ti): Recovering Ilmenite

- 5. Nickel (Ni): Sulfide and Laterite Processing

- 6. Cobalt (Co): Strategic Battery Metal Recovery

- 7. Selecting the Right Equipment for the Job

- 8. Summary Comparison Table

- 9. Frequently Asked Questions

- 10. References

1. The Science of Magnetic Susceptibility

To understand which metals separated by magnetic separation are viable for commercial processing, one must first understand magnetic susceptibility. This is the measure of how much a material will become magnetized in an applied magnetic field.

We generally categorize minerals into three groups:

- Ferromagnetic: Strongly attracted to magnets (e.g., Magnetite). These are easily recovered with low-intensity separators.

- Paramagnetic: Weakly attracted to magnets (e.g., Hematite, Ilmenite). These require high-intensity magnetic fields, often exceeding 10,000 Gauss.

- Diamagnetic: Repelled by magnets (e.g., Quartz). These end up in the tailings.

The success of the separation process depends on selecting the right equipment to match the specific susceptibility of the target metal.

2. Iron (Fe): The Ferromagnetic Standard

Iron is the primary metal associated with this technology. However, from our operational experience, treating all iron ore the same is a recipe for yield loss. We must distinguish between the mineral forms of iron to select the correct machinery.

Magnetite (Fe3O4)

Magnetite is strongly ferromagnetic. For this mineral, low-intensity magnetic separation (LIMS) is sufficient. Standard drum separators operating between 800 to 1200 Gauss effectively recover magnetite concentrate. In waste recycling, “tram iron” (scrap steel) is also easily removed using basic Plate Type Permanent Magnetic Separation Equipment to protect downstream crushers.

Hematite (Fe2O3) and Limonite

These are weakly magnetic (paramagnetic). A standard magnet will not capture them efficiently. We recommend using High Gradient Magnetic Separators (HGMS) or a Wet High Intensity Magnetic Separator. These machines generate fields up to 20,000 Gauss to induce magnetism in the weak iron particles, ensuring high recovery rates from tailings that would otherwise be discarded.

3. Manganese (Mn): The Paramagnetic Challenge

Manganese is a critical component in steelmaking and battery production. Unlike iron, manganese minerals such as Pyrolusite and Rhodochrosite are generally paramagnetic. Separating manganese requires a nuanced approach because its magnetic susceptibility is significantly lower than magnetite.

From our experience, dry magnetic separation is often used for coarse manganese ores, while wet high-intensity separation is preferred for fines to avoid dust and improve grade. Utilizing a Wet High Intensity Magnetic Separator allows for the precise removal of silica and other diamagnetic impurities from the manganese concentrate. The key here is field strength; operating below 12,000 Gauss typically results in poor separation efficiency for manganese.

4. Titanium (Ti): Recovering Ilmenite

Titanium is rarely found in its metallic form; it is processed from minerals like Ilmenite (FeTiO3) and Rutile. Ilmenite is the most important ore of titanium and happens to be paramagnetic.

In heavy mineral sand deposits, magnetic separation is the standard method for separating Ilmenite from non-magnetic Rutile and Zircon. We recommend a multi-stage approach:

- Low Intensity Stage: Remove highly magnetic Magnetite to prevent clogging downstream.

- High Intensity Stage: Use a high-gauss separator to capture the Ilmenite.

- Electrostatic Separation: Final cleaning of the concentrate.

The separation of titanium-bearing ores is a classic example of where metals separated by magnetic separation require a deep understanding of mineralogy to maximize economic return.

5. Nickel (Ni): Sulfide and Laterite Processing

Nickel presents a unique challenge. In its metallic form, it is ferromagnetic, but in nature, it is often found in laterite soils or sulfide ores (Pentlandite). Pentlandite is usually associated with Pyrrhotite, which is magnetic.

When processing nickel sulfide ores, magnetic separation is used to reject the magnetic Pyrrhotite, which often contains low nickel values and high iron content, or to concentrate the Nickel if it is structurally bound to the magnetic fraction. For ferro-nickel slag recovery, standard drum separators are highly effective. We have seen significant success using the 1.1kw Belt Magnetic Separator for recovering nickel alloys from industrial slag and crushed waste, providing a high-purity scrap product for remelting.

6. Cobalt (Co): Strategic Battery Metal Recovery

Cobalt is ferromagnetically similar to iron and nickel but typically requires higher field strengths due to its mineral associations. It is often a byproduct of Copper or Nickel mining. In recycling applications, such as Lithium-ion battery recycling (black mass processing), magnetic separation plays a crucial role.

The casings of batteries are often steel (ferrous), while the cathode material contains Cobalt and Nickel. By shredding batteries and passing them under a magnetic separator, the steel casings are removed first. Subsequent high-intensity separation steps can help fractionate the remaining materials based on their varying magnetic susceptibilities. As the demand for EV batteries grows, the list of metals separated by magnetic separation increasingly highlights Cobalt as a priority.

7. Selecting the Right Equipment for the Job

Choosing the correct equipment is not just about the metal; it is about the process state (wet vs. dry) and the particle size. ORO Mineral Co., Ltd. has been manufacturing intelligent mineral processing equipment since 2014, and based on our rich experience, we categorize equipment selection as follows:

For Coarse, Strongly Magnetic Materials

If you are removing tramp iron from a conveyor belt or processing coarse magnetite, a Belt Magnetic Separator is ideal. Specifically, the 1.1kw Belt Magnetic Separator offers a robust balance of energy efficiency and field depth, ensuring that heavy iron pieces are pulled out of the material flow before they damage crushers.

For Protection and Purification

In food processing, plastics, or ceramic industries where the goal is product purification rather than ore concentration, Plate Type Permanent Magnetic Separation Equipment is the industry standard. These are installed in chutes to capture fine iron contaminants.

For Fine, Weakly Magnetic Ores

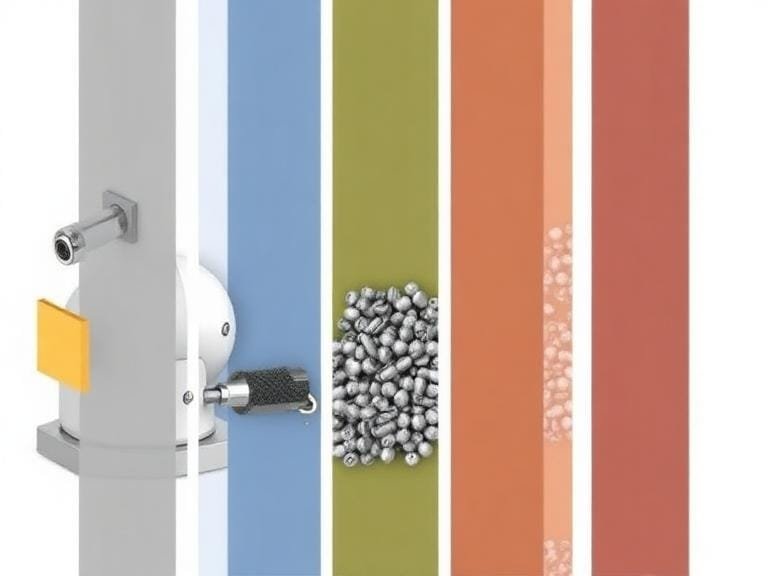

This is the frontier of modern mineral processing. For Hematite, Limonite, Manganese, and Ilmenite, a Wet High Intensity Magnetic Separator (WHIMS) is non-negotiable. These machines use a matrix (like steel wool or rods) inside the magnetic field to create high-gradient zones that capture micron-sized paramagnetic particles. Without WHIMS technology, millions of tons of valuable metal would be lost to tailings ponds.

Expert Insight: The Importance of R&D

At ORO Mineral, we integrate R&D with production. We have found that “off-the-shelf” solutions often fail because ore bodies vary globally. We recommend testing your ore samples to determine the precise magnetic gauss required for liberation. Sparing no effort to improve technology and develop new equipment is how we ensure high recovery rates for our clients.

8. Summary Comparison Table

| Metal/Mineral | Magnetic Property | Recommended Equipment | Typical Gauss Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron (Magnetite) | Ferromagnetic (Strong) | Drum Separator / Belt Separator | 800 – 1,500 Gauss |

| Iron (Hematite) | Paramagnetic (Weak) | Wet High Intensity Separator | 10,000 – 15,000 Gauss |

| Manganese | Paramagnetic (Weak) | High Gradient Magnetic Separator | 12,000 – 18,000 Gauss |

| Titanium (Ilmenite) | Paramagnetic (Weak) | High Intensity Roll Separator | 10,000 – 20,000 Gauss |

| Nickel (Slag/Alloy) | Ferromagnetic | Drum / Belt Separator | 1,500 – 3,000 Gauss |

| Cobalt | Ferromagnetic | Cross Belt Separator | 3,000 – 6,000 Gauss |

9. Frequently Asked Questions

Can Copper be separated by magnetic separation?

Generally, no. Copper is diamagnetic (repelled by magnets). However, magnetic separation is often used in copper processing to remove iron contaminants (tramp iron) or to separate copper ores from associated magnetic minerals like Magnetite or Pyrrhotite.

What is the difference between wet and dry magnetic separation?

Dry separation is used for coarse materials and free-flowing moisture-free ores. Wet separation is used for fine particle sizes (below 3mm) and involves mixing the ore with water to form a slurry. Wet separation is more efficient for fine particles as it cleans the concentrate better and reduces dust.

Why is a Wet High Intensity Magnetic Separator necessary for Hematite?

Hematite is only weakly magnetic. A standard magnet is not strong enough to overcome the forces of gravity and drag on the particle. A Wet High Intensity Magnetic Separator generates a massive magnetic field and uses a matrix to create gradients that trap these weak particles.

How does ORO Mineral ensure equipment quality?

Since 2014, ORO Mineral has focused on integrating R&D with production. We test our 1.1kw Belt Magnetic Separator and other units rigorously against solid waste resource recovery and mineral screening standards to ensure longevity and performance.

10. References

- Svoboda, J. (2004). Magnetic Techniques for the Treatment of Materials. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Wills, B. A., & Finch, J. (2015). Wills’ Mineral Processing Technology. Butterworth-Heinemann.